The first post in this 3-part mini-series introduced the community-led conservation hub movement. This second post briefly looks at the community conservation sector in Aotearoa and what makes it so unique – that’s key to why hubs developed. It’s worth pointing out that there isn’t a one-size-fits all hub model, so how each hub actually came into being is very time and place-specific. The post wraps up with an outline of hub activities: their mahi both with and for their member/affiliate groups and communities as well as the benefits they provide.

Community conservation in Aotearoa is unique. Having been involved in the sector for over two decades and having travelled widely overseas, there just isn’t the same strong, cohesive grassroots approach to conservation elsewhere. What’s fascinating here, is how small groups operating more or less independently from one another, identify with the wider community-led conservation movement. They’re part of something much, much bigger than themselves – unknown numbers of groups and projects that are spread across public and private land, from urban backyard initiatives to vast landscape-scale projects in remote corners of the motu. Most groups/projects restore degraded sites (e.g., through pest and weed control, planting natives and reintroducing missing fauna) as well as protect them (e.g., through advocacy, education and submitting to govt. agency plans). Because there’s usually limited capacity within groups to operate beyond the scope of their own projects, regional events are vital for building cohesion and contributing to momentum. There’s typically an impressive turnout at annual events such as Wellington’s Restoration Day and at quarterly Pest Liaison Group meetings in Auckland. Among presentations from conservation professionals, workshops and fieldtrips, groups have the opportunity to showcase their projects and build their networks with other community groups, land managers, service providers and other conservation players.

Streamlining conservation delivery

Groups’ conservation and restoration works certainly wouldn’t happen without their good will, determination, strong backs – and for paid staff, often low wages. However, contestable grants pit groups against each other for limited, and are mostly heavily oversubscribed. Additionally, groups need to be registered as a trust or society to apply for many enviro-centric grants, which means there are hundreds of small charitable organisations in the environmental sector alone. The annual paperwork required is a burden on small groups, and sourcing funding for admin-type roles is a perennial issue.

“The invisible support, knowing that you are part of a larger organisation is extremely valuable. Being part of [name of hub] enables us to contemplate far larger projects because we are not alone, they have the resources which a small community groups has difficulty obtaining” (Survey respondent, 2021).

Enter hubs. Essentially the focus is to streamline community-led conservation and to strengthen community conservation impact. Julian Fitter, Chair of the Māketu Ōngātoro Wetland Society (originally from the UK), wondered why we didn’t have an efficient community conservation model analogous to that of the UK Wildlife Trusts. The number of conservation initiatives in the Bay of Plenty each operating independently and largely unsupported by any overarching non-government organisation was one of the drivers behind establishing the Bay Conservation Alliance (BCA).

Growing a hub

BCA was founded in 2017 and now has over 20 member groups which receive support for environmental education program design and delivery, financial management, group/project administration and operations, advocacy, fundraising, networking and accessing contractors. In this case, BCA was set up to fulfil a specific gap in the region – as was Predator Free Hauraki Coromandel Trust (est. 2017). Other hubs have morphed from small groups/projects over extended timeframes – the Banks Peninsula Conservation Trust (BPCT) is a good example. The organisation was established in 2001 through a mediated environment court settlement which resulted from strong landowner distrust following the District Council approach to protecting Significant Natural Areas on Banks Peninsula. BPCT have evolved over two decades into a large-scale organisation supporting groups and individual landowners as well as running a range of projects. While still firmly community-led, organisational structure, the scope of operations and diversity of partnerships differ considerably from the original BPCT.

Community groups and hub activities

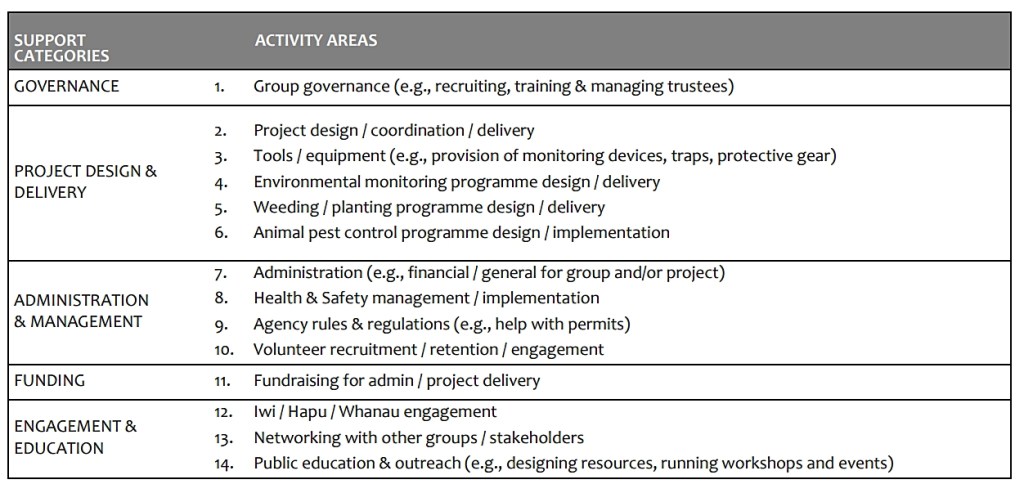

Community conservation groups operate in many different ways – size is just one factor. Below is a summary of what a group may carry out, which also includes areas hubs may provide support and hands on assistance for:

However, hubs provide much, much more than a range of direct services for their member/affiliate groups. Research (i.e. interviews, focus groups and questionnaires with hub managers, trustees and member/affilate groups) carried out 2020-2022 reveals a much broader range of actions and associated benefits:

- Hubs create efficiencies in conservation delivery by avoiding reinventing the wheel (e.g., providing templates; plans and policies) and assisting with basic admin.

- Authority is conferred to hubs as independent, community-led conservation organisations so they can serve simultaneously as a buffer and communication channel between agencies and community groups.

- Hubs operate as a primary point of contact for the community due to their positioning as regional/sub-regional community conservation support providers.

- Several hubs operate grants programs for their member/affiliate groups.

- Some hubs build community group/conservation capacity by running workshops, providing training and other learning opportunities.

- With hubs sharing best practice and tools such as Trap.nz consistency and cohesion in conservation delivery is promoted.

- Hubs enhance the profile of community-led conservation by informing the public about conservation issues and their member/affiliate groups’ projects.

- Hubs help enhance the profile of individual member/affiliate groups and community-led conservation as a whole.

- Hubs foster community conservation connections, by growing networks and supporting leadership.

What comes next?

The first post in this miniseries (1/3) introduced the concept of community-led conservation hubs. The last post (3/3) will cover what success looks like for hubs and will outline what the determinants of success are along with impact measures.

Further reading

Doole, M. (2020). Better together? A review of community conservation hubs in New Zealand. Report for Predator Free NZ Trust. 23p

McFarlane et al. (2021). Collective Approaches to Ecosystem Regeneration in Aotearoa New Zealand. Cawthron Report No. 3725. 96p

Peters, M. A. (2019). Understanding the Context of Conservation Community Hubs. Report for the Department of Conservation. 44p

Peters, M. A., and Denyer, K. (2021). Special Fund Allocation to Community Conservation Hubs: Establishing a baseline to understand the impact of funding on hubs’ member/affiliate groups. Report for the Department of Conservation. 26p

Peters, M. A. (2022). Special Fund Allocation to Community Conservation Hubs: Second Report. Report for the Department of Conservation. 22p

Pingback: Community-led conservation hubs: Determinants of success and measuring hubs’ impact (Part 3 of 3) | monicalogues·

Another strand of community group development was initiated by Richard Hursthouse soon after he initiated the establishment of PFK (The Pest Free Kaipātiki Restoration Society on Auckland’s North Shore).

He saw the need for good quality integrated software to support both ecological work and relationship development.

He spearheaded the establishment of the EcoNet.NZ Charitable Trust which has now implemented the CAMS group management system in several conservation groups using Dynamics CRM.

In parallel EcoNet worked with STAMP to implement the CAMS Weed App which can support both STAMP’s spectacular crowd sourced volunteer weed control and community group led weed control and education programmes.

The EcoNet.NZ strategy enables community conservation groups to leverage their people skills and knowledge to reach a wider community and achieve improved outcomes.

It can reduce the tedious collation of reports and other routine administration extending the group’s ability to use modern processes and systems to develop more effective teamwork.

LikeLike