Our conservation landscape has undergone some radical changes and community-led conservation hubs are thriving. I first blogged about hubs in 2020, describing what they are, how they operate and what they do. Part of the research I’ve been involved with over the last few years (see references at the end of this post) has been determining their impact. Their collective mahi and passion are so inspiring but how can their achievements, socially and environmentally, be measured? This blog draws from the research, redefining what they are, highlighting the complexity of the political and economic landscapes hubs operate within and delving a little into their diversity. Follow-up blogs will cover their history, roles and successes.

There’s a bewildering array of terminology Aotearoa describing organisations that support the work of other, mostly smaller conservation groups and their projects. Casting the net widely across the motu, at a glance there are (1) national networks – societies and trusts hosting annual conferences (e.g., the National Wetland Trust); (2) national programs that provide training and conservation/education experiences (e.g., Mountains to Sea Conservation Trust); (3) regional hubs networks and programs such as Biodiversity Fora, and (4) sub-regional hubs, networks and programs including Environment Centers. But I’m going to zoom in a bit and define hubs like this:

“A community-led organisation designed to strengthen and support community-led environmental groups and individuals situated within a defined geographical area by providing practical support, coordination, leadership and strategic oversight of regional/subregional conservation needs and opportunities“.

They’re so much more than a network, collective or collaboration of formalized and informal community environmental groups and projects, stakeholders and partners. While hubs mostly support individual groups and their projects, they also support landowners and collectives of community groups/ organisations running larger projects within the geographical reach of the hub.

A conservation snapshot across Aotearoa: 2019 – 2023

In 2020, I questioned whether hubs will make a difference. It’s not just their physical growth since then (e.g., employing more staff) it’s also their maturation. There are two components here – one centres on internal processes, the other on services and programmes provided to the community. But the latter is in response to the external variables: look at what’s happened since 2019! Conservation has shifted seismically as has the operating environment.

Community-led conservation has become bigger, bolder and much, much more ambitious. Many initiatives have expanded across the landscape, filled gaps left by agencies, and strengthened their socio-cultural and ecological focus. Conservation has spread into cities, while new technologies like eDNA kits allow communities to collect data cheaply and efficiently. Investment via Predator Free 2050, Jobs for Nature, philanthropic and other sources has fostered the development of more complex projects and programs, stitching multiple partners together – NGOs, Not-for-Profits, iwi, agencies and business. Iwi voices are becoming stronger as conservation is redefined and reimagined within te ao Maōri and not just through western science paradigms.

E hara taku toa i te toa takitahi, he toa takitini …My strength is not as an individual, but as a collective

New plans, policies and strategies shape the direction and context for conservation: Te Mana o te Taiao – Aotearoa New Zealand Biodiversity Strategy 2020 is designed to protect, restore and sustainably use our biodiversity (a National Policy Statement for Indigenous Biodiversity is in the wings); there’s the National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management 2020 (which includes wetlands), and the overarching National Adaptation Plan for Climate Change developed in 2022. The long overdue overhaul of the Resource Management Act 1991 will also help build a better foundation for our environment going forward in a climate changed world.

What do hubs look like?

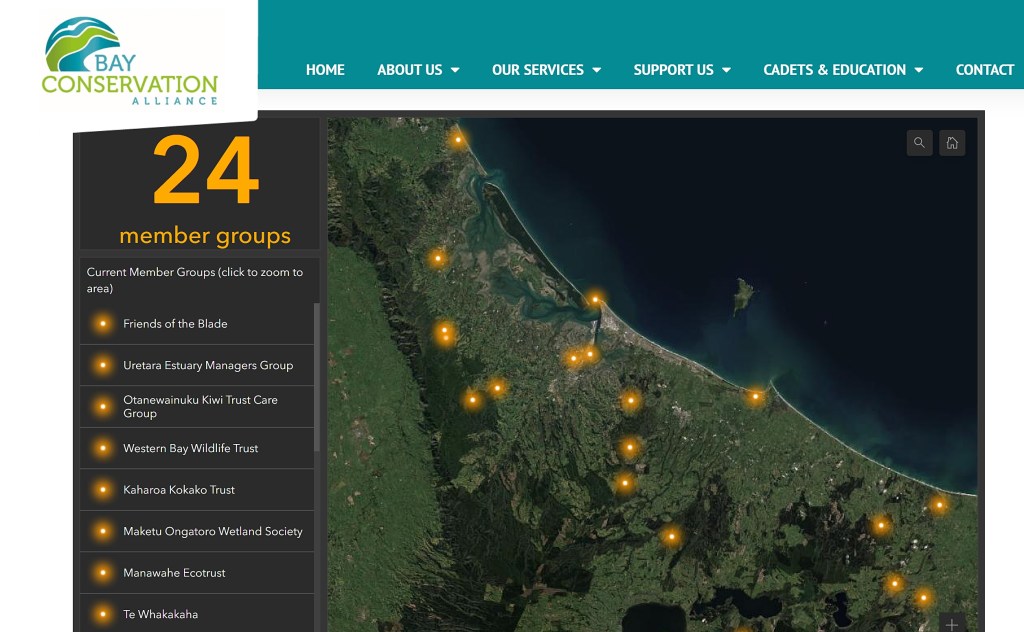

The key to their success is their responsiveness to their local area: the landscape and associated environmental issues, the communities that live there, local iwi and land management agencies and so forth. There just isn’t, and can’t be, a one-size-fits-all hubs model. Their size varies – some cover the whole region (e.g., Wild for Taranaki/WfT, Bay Conservation Alliance/BCA in the Bay of Plenty, Biodiversity Hawkes Bay/BHB and Tasman Environmental Trust/TET) while others are sub-regional in line with special geographical features (e.g., Banks Peninsular Conservation Trust/BPCT in Canterbury and Predator Free Hauraki Coromandel Community Trust/PFHCCT in the Waikato). All have some paid staff and source funding from contestable government grant schemes (e.g., MfE, DOC and Regional Councils), community trusts businesses and others. Some have fee paying members (e.g., BCA and WfT) while others have affiliated groups and projects (e.g., BPCT, PFHCCT and TET). Some hubs employ staff to run specific projects, while others focus on supporting groups to run their own conservation/restoration initiatives.

What next?

Given the complexity of hubs, and to do them justice(!), I’ve broken down content like this:

- Hubs blog Part 2 will cover hub development and the roles that hubs play in community-led conservation.

- Hubs blog Part 3 will cover what success looks like and determinants of success.

Further reading

Doole, M. (2020). Better together? A review of community conservation hubs in New Zealand. Report for Predator Free NZ Trust. 23p

McFarlane et al. (2021). Collective Approaches to Ecosystem Regeneration in Aotearoa New Zealand. Cawthron Report No. 3725. 96p

Peters, M. A. (2019). Understanding the Context of Conservation Community Hubs. Report for the Department of Conservation. 44p

Peters, M. A., and Denyer, K. (2021). Special Fund Allocation to Community Conservation Hubs: Establishing a baseline to understand the impact of funding on hubs’ member/affiliate groups. Report for the Department of Conservation. 26p

Peters, M. A. (2022). Special Fund Allocation to Community Conservation Hubs: Second Report. Report for the Department of Conservation. 22p

Pingback: Community-led conservation hubs: From evolution to action (Part 2 of 3) | monicalogues·

Pingback: Community-led conservation hubs: Determinants of success and measuring hubs’ impact (Part 3 of 3) | monicalogues·