Birds, the taonga of the skies were the inspiration for an expansive Orchestras Central concert, hosted once again by the University of Waikato at the Gallagher Centre of Performing Arts. Flights of Fancy invited us to travel across international waters and time zones, from Baroque Italy to Aotearoa of the past and present. Compositions from Vivaldi, and our own Anthony Ritchie, Janet Jennings and Bjorn Arntsen, variously intrigued, challenged and awed the audience. Again, my role was both as emcee and presenter (see here for the World Concert). With the go-ahead from the Orchestras Central crew, I shaped my words, gestures and images around the aerial theme… neat pillbox hat, swirly kerchief knotted over one shoulder, dress and pumps, I became the flight attendant, creative prompter and science advisor for the evening. The following post is adapted from my presentation.

So, our journey of sound and image began, fittingly, with a safety briefing. Tray tables up, phones on flight mode, a warning of potential turbulence, given the emotional nature of the music – after all, this was a performance designed to stir. And like any long-haul flight, refreshments were promised—though only in the form of cultural nourishment.

On our departure from Baroque Italy this evening

The evening opened in Baroque Italy with Vivaldi’s Cuckoo (Concerto for violin, strings & b.c. in A major RV 335). Rather than share the unique ecology of our avian counterparts in Europe, I opted to share how our own koekoeā (long-tailed cuckoo) and pīpīwharauroa (shining cuckoo), lay their eggs in the nests of the tiny riroriro (grey warbler). As unwitting foster parents, riroriro raise the chicks – alarmingly much larger than themselves. They’re fed tirelessly until the cuckoos’ biological alarm sounds, and their internal radar sends them migrating thousands of kilometres across the Pacific.

The next leg of our flight celebrates our native species… and their curiosities

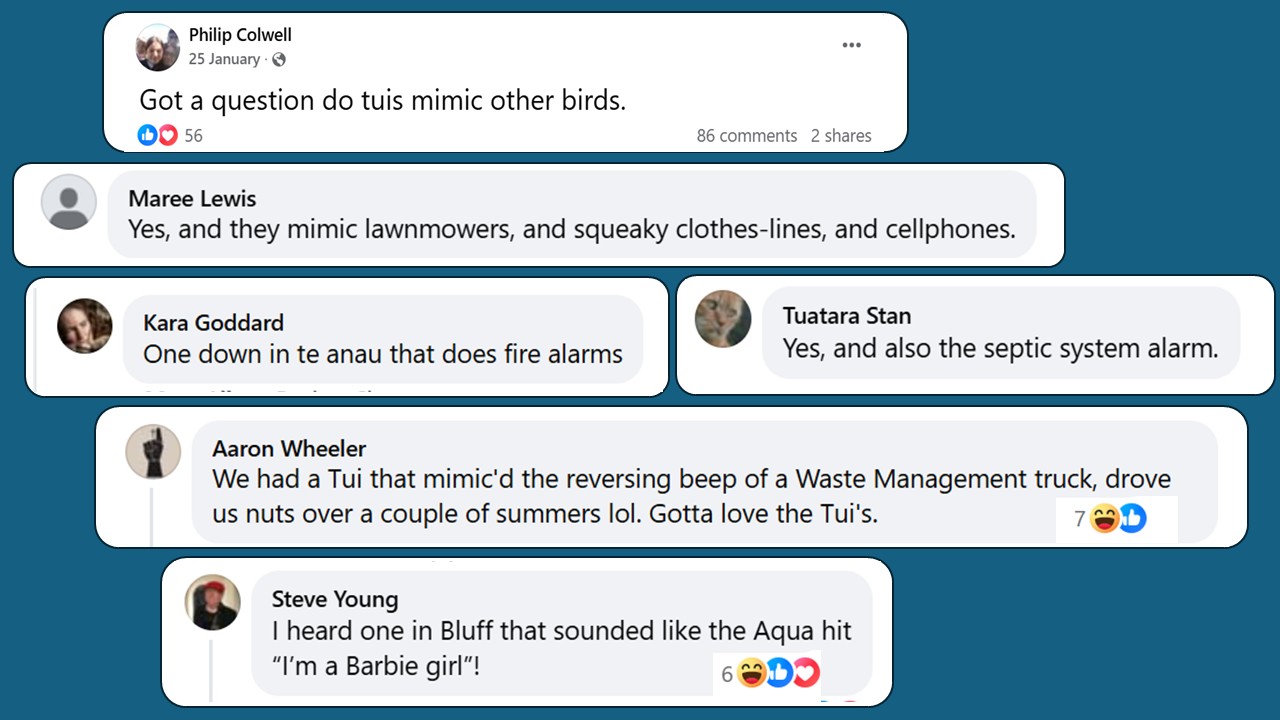

Where the cuckoo is best known for hand’s off parenting, the tūī is lauded for its aerial and vocal acrobatics. Anthony Ritchie’s work – Tui for solo flute Opus 109 (2004), celebrated this bird of dual voice boxes. What compels a bird to sing? proclaiming territory; sharing warnings, sweet talking a mate, or just advertising presence? For tūī it seems to be avian fun. As expert mimics, they delight, baffle and at times exasperate humans within earshot. I had enormous fun scrolling through a Facebook feed, finding choice commentary:

Shortly we’ll be landing in the Aotearoa Extinction Era

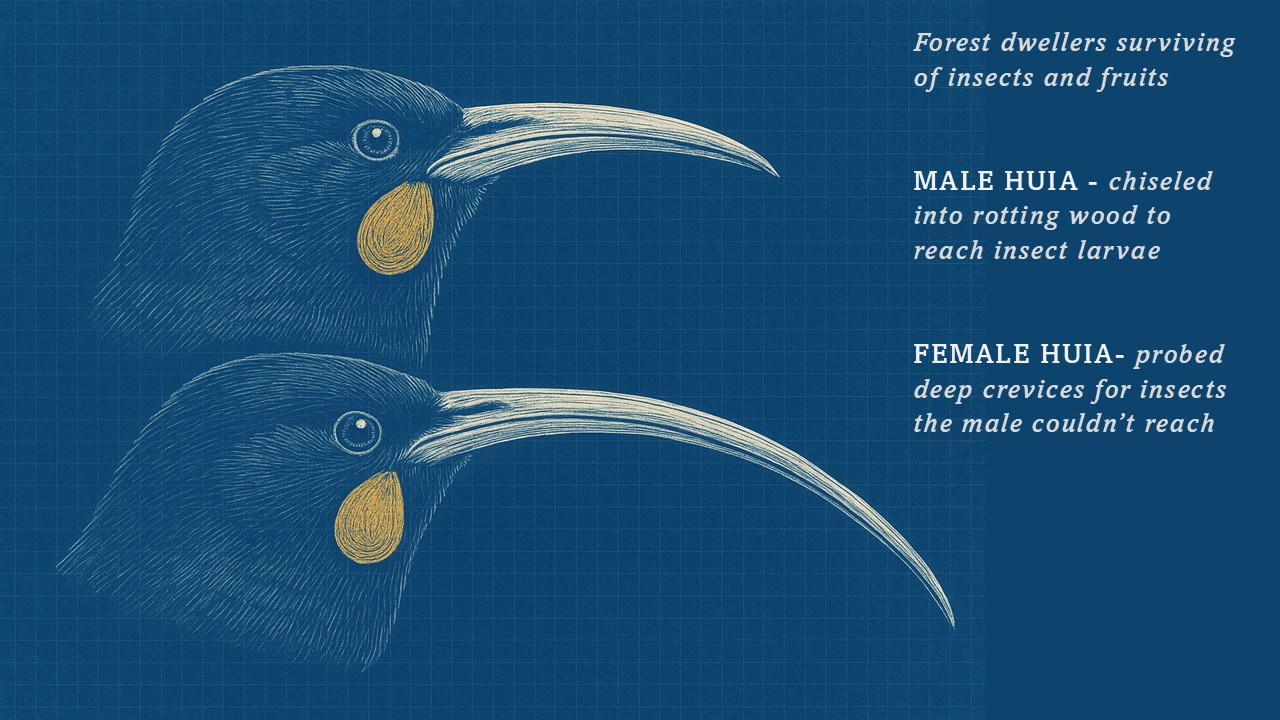

In this era, science, evolution, legend, imagination and music coalesce. Composer Janet Jennings‘ work The Lost Birds of Aotearoa (string quartet, 2023) honoured four extraordinary birds:

- Moa waewae taumaha (heavy-footed moa), a giant with legs like a rugby prop, gone by 1500

- Whēkau (laughing owl), its eerie cry silenced by stoats and ferrets by the early 1900s

- Pouākai (Haast’s eagle), talons the size of a tiger’s claws, wings spanning metres across, vanished with the moa it preyed upon

- Huia, with its paired his-and-hers beaks and tail feathers once treasured, hunted into oblivion last century

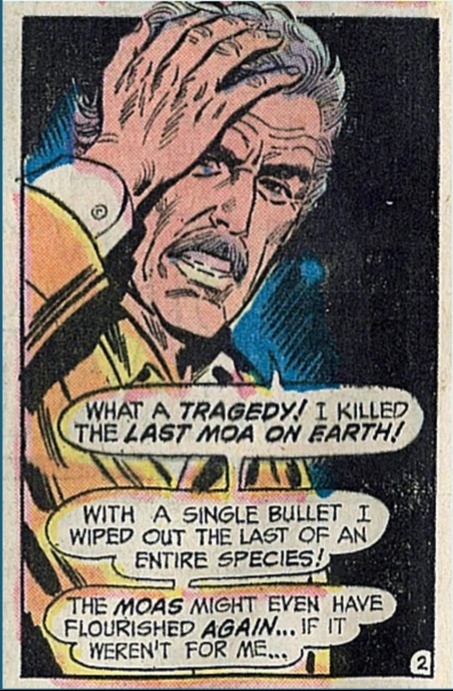

Of the whēkau and huia we know some of their calls, their habits the ecosystems they once thrived in. But fragments of bone and feather, occasional mummified pieces along with pūrākau, traditional stories are all that we have from the earliest species. It occurred to me that it is easy to avoid any responsibility for birds made extinct generations ago, but what if an extinction occurred on our watch? A bizarre 1973 Superman comic creates this exact scenario. What if a moa had survived, and was accidentally dispatched by modern man… how might we feel about that?

Prior to our departure from Aotearoa…

We were privileged to experience the world premiere of Bjorn Arntsen’s Maru for strings and harpsichord (2024 Tertiary Winner Composition Workshop competition in collaboration with University of Waikato). The work was inspired by a familiar phenomenon: a repeated sound lodged in our brains, looping, an aural itch that needs constant scratching. Sometimes it’s soothing, other times unsettling. Talking to Bjorn prior, he mentioned he’d been toying with the same sound loop – known as an earworm for almost 20 years. I reflected on bird calls. Some of our species share a simple repetitive sequence – the ruru with its two-note call, the murmuring coo coo of a kererū or the grey warbler, warbling its little melody. There’s some good science around the calming effect that natural repeated sounds like bird calls have on our psyche – they evoke safety and connection to nature.

On our return to Baroque Italy…

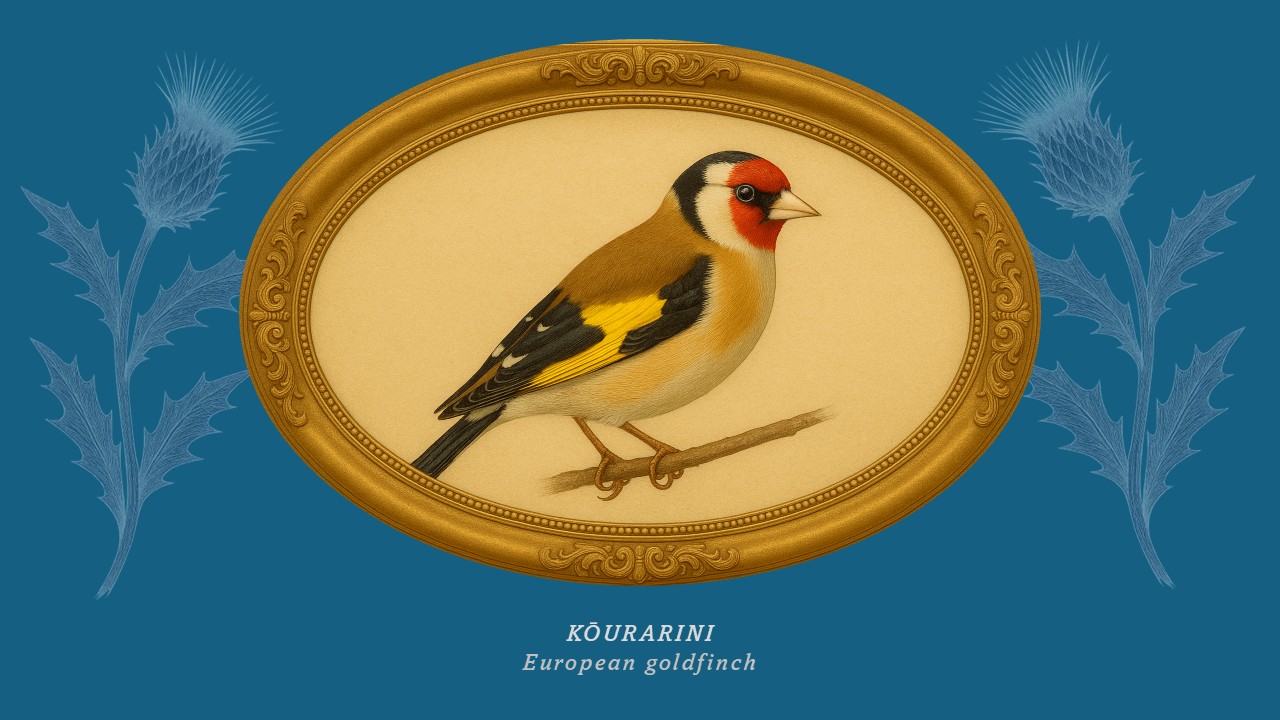

Two works from Vivaldi – the Concerto for flute in D major, (Op. 10, No. 3), and Concerto for Violin in A minor (RV 356) comprised the final leg of the journey. The Goldfinch (which inspired the first work), was brought to Aotearoa by early settlers as a feathered souvenir, a reminder of a home on a distant shore. Uncountable numbers of exotic birds now form part of our local soundscape: squabbles of sparrows, murmurations of starlings, and chattering hordes of those fruit tree vandals, eastern rosellas. Of the staggering 130 bird species introduced to Aotearoa from the mid-1800s, 41 have made themselves at home… but many have negative impacts on our native flora, fauna, crops and ecosystems.

Flights of Fancy: wrapping up our journey

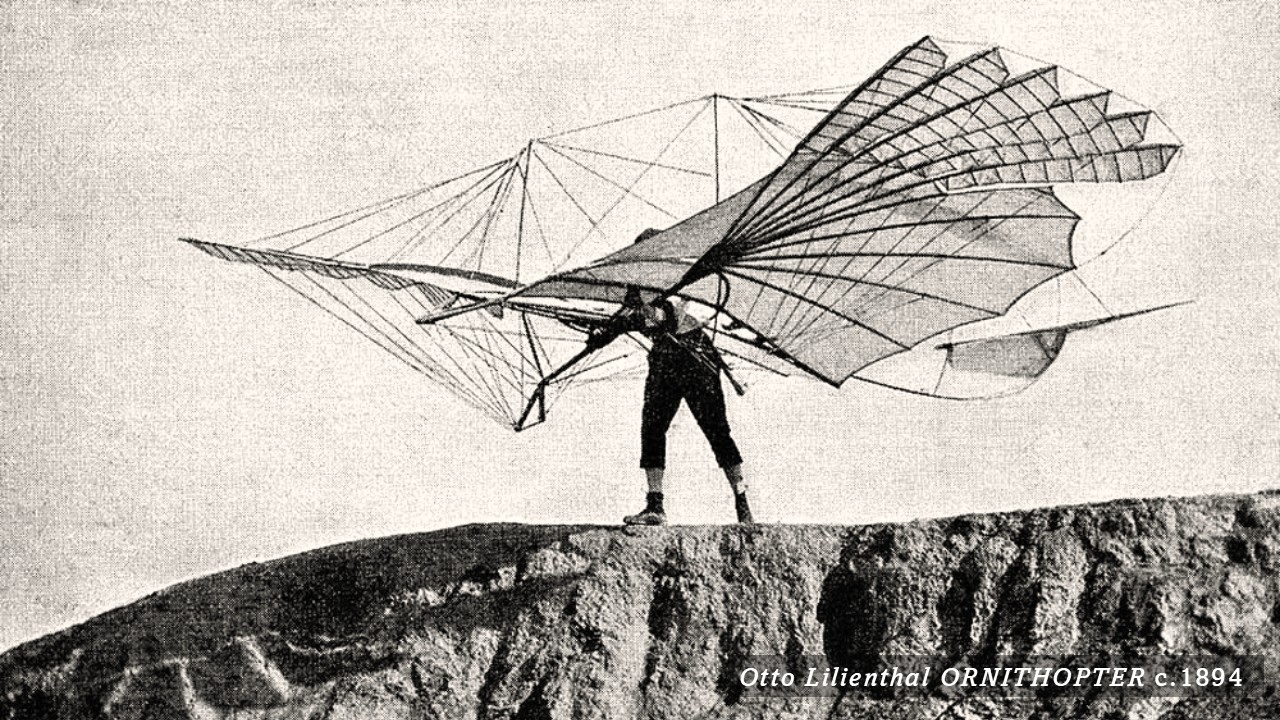

Flying like a bird has been a human desire for centuries. A breakthrough occurred in the 1700s with the invention of hot air balloons. Powered flight arrived in the early 1900s, yet on a timescale with birds, humans are evolutionary latecomers to the skies. The reptilian Archaeopteryx was surveying land and prey from above – some 150 million years ago.

Whether ancient, extinct or in our forests and gardens, birds are as deeply embedded in our environment, as they are in our culture, history, and language. In Aotearoa they form the symbols of our national identity, adorn our currency, stamps, accessories, and homewares. They are woven throughout pūrakau, myth and legend, and have helped us understand the uniqueness and superb strangeness of our remote island ecology.

The evening was an invitation for the audience to enjoy the merging of music, science, history, evolution and creativity. As both emcee and presenter, the opportunity to complement and expand the program through narrative and image was both a privilege and enjoyable challenge. The return flight across international waters and time zones was a superb exploration of how music can transport us into the world of birds – achieved with aplomb by the very talented Orchestras Central crew.