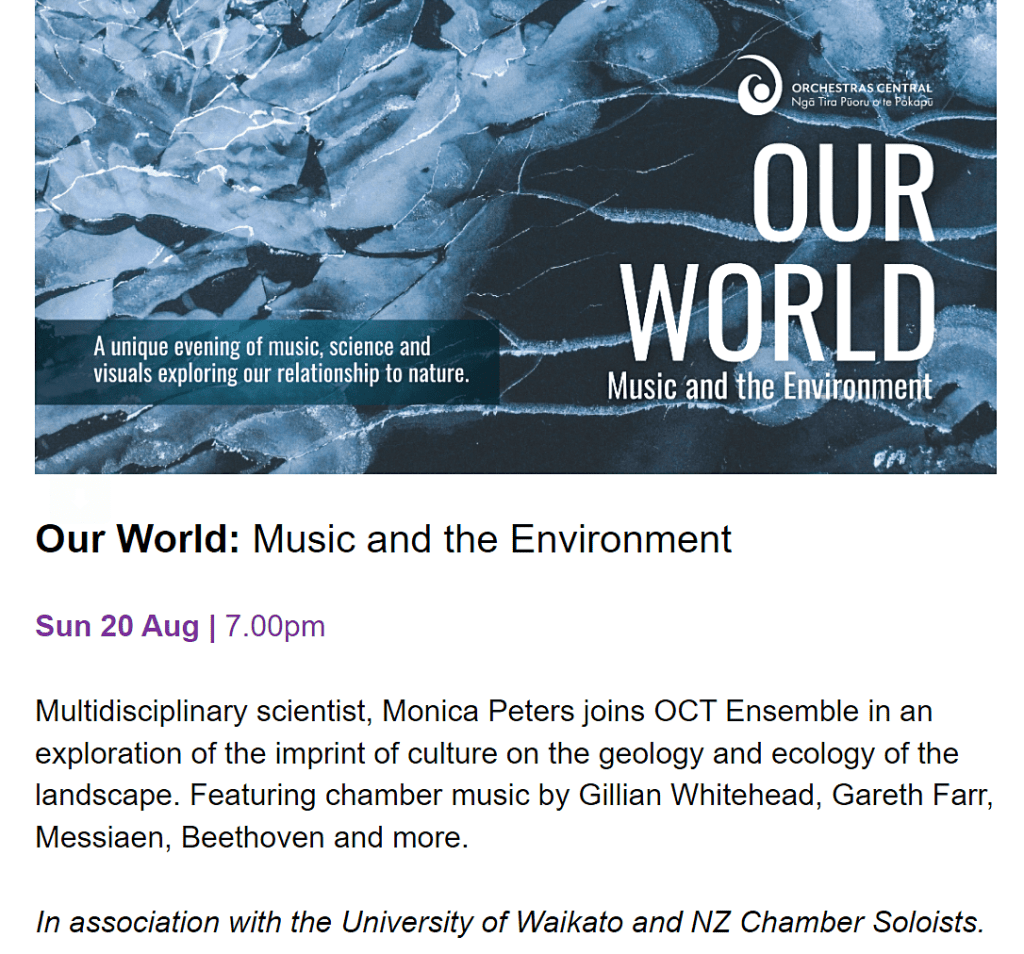

It’s not often I’m given free rein to speak about art, music, sound, and science all at once… Orchestras Central Trust invited me as the speaker & informal MC to Our World, an end of festival premier event, wrapping up a month of concerts and workshops. My initial brief was to talk about science, nature and the environment by way of complementing the environmental theme of the event: 7 works, 3 by NZ composers with content spanning centuries, musical genres, different ecosystems and even species. But with my eclectic background, the simple speaking part became two short narrative forays incorporating images, observations, musings, anecdotes… and a little poetry.

The music

Orchestras Central is a community trust that exists to inspire and bring joy to people across the Waikato region through sharing music. The evening’s repertoire was a meditation on nature, with the evocative Ngā hā o neherā for solo bassoon by Dame Gillian Whitehead opening the event. Messiaen’s quirky Blackbird for piano and flute (he was a keen ornithologist) was followed by the first public performance of Low Ceiling, an award-winning work by Waikato University’s Bjorn Arnsten.

Dunedin composer Anthony Ritchie‘s Octopus, took players through the whole lifecycle while the aurally challenging Vox Balanae, a George Crumb work, incorporated cello notes eerily resembling humpback whale calls. The final two works took listeners from the Jurassic forests of Northland for Gareth Farr’s work – Waipoua, to the bucolic rural idyll of Beethoven.

relationship to the natural world

Narrating a journey through different genres

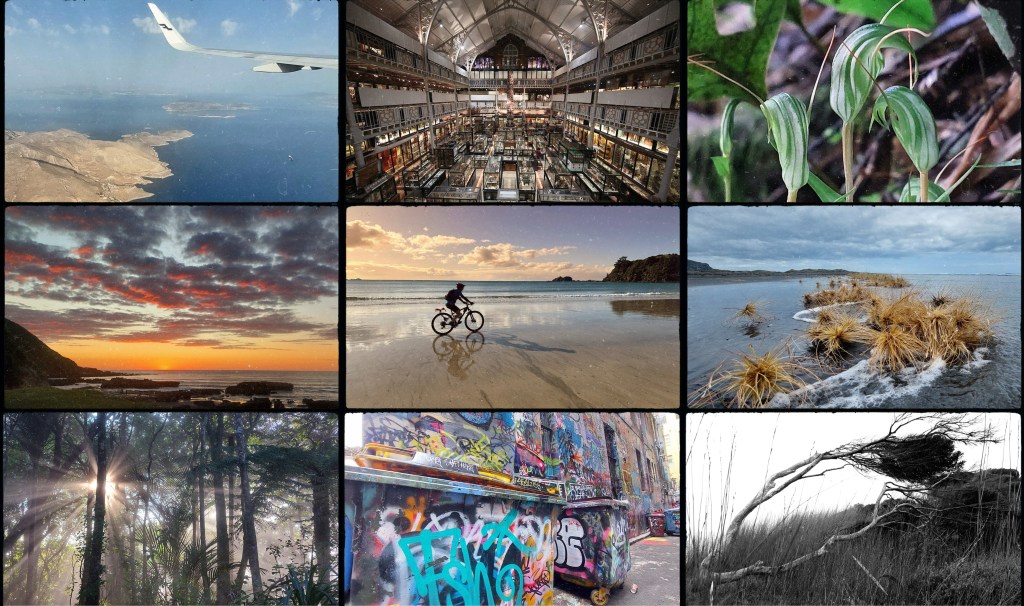

How to complement these works? How to offer the audience a chance to pause and reflect on sound, nature and different ways of experiencing the world? My starting point was that music, art and science intersect on so many levels – far beyond one just providing inspiration for the other. Over the course of the evening, I shared meeting a PhD student studying the digestive system of aphids. At the time, I was struck by the astounding smallness of the topic, completely at odds with the richness, scale and complexity of the natural world. It hit home then, just how radically different sensory and intellectual experiences of the world can be, and how these can be moulded by the disciplines we choose to pursue.

Art should comfort the disturbed and disturb the comfortable – Mexican poet and academic, Cesar A. Cruz

Similarly, when I questioned a composer of experimental works about her process of music-making – she simply replied, “I listen for the harmonies”. Because listening to juxtapositions of sounds that sit outside comfortable convention (and there was plenty of that over the course of the evening), is an opportunity to reassess and re-evaluate the experience of hearing and listening. To the concert audience, I described a fundamental tension: on one hand being open and free from preconceptions, being able to float untethered, while on the other understanding the desire or need to remain anchored, to what is tangible and familiar.

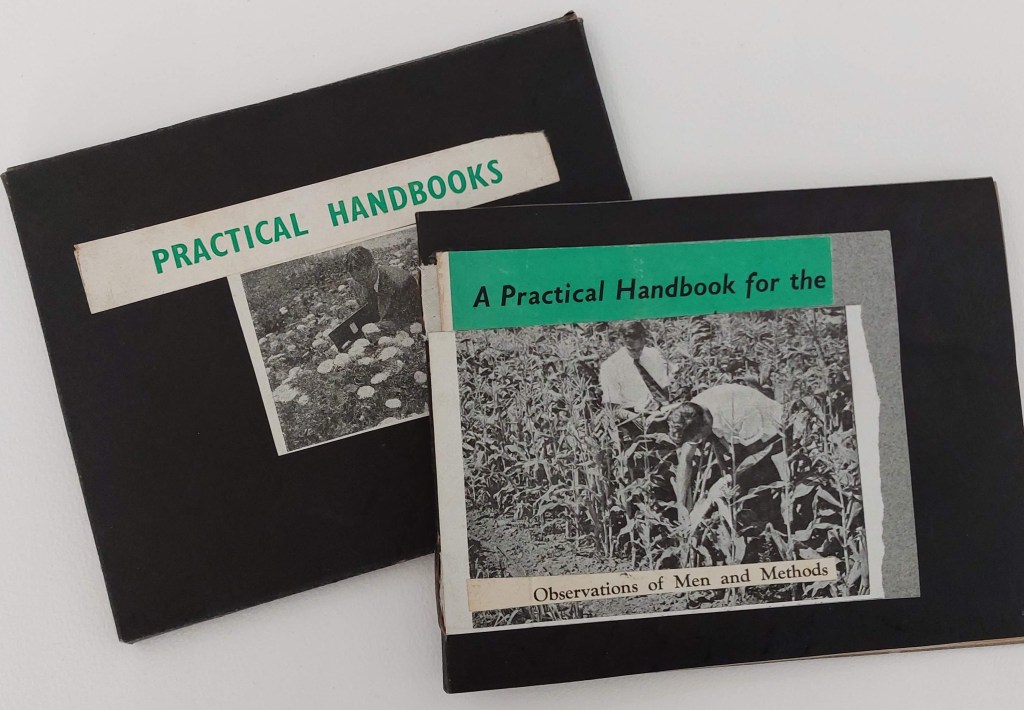

scientific guides for plant cultivation

The art, and the science

In my world, both art and science are tools for exploring the environment, the way we relate to it and structures we overlay to investigate and interpret it. As an artist I mainly draw, and in the past, have made prints, all ephemeral works on paper. As a scientist, I’ve designed studies, measured, collected data, categorized, analysed, interpreted, and drawn conclusions. From time to time, the two disciplines also merge and inform each other: as observer and critic with my fine arts hat on and unraveled details as a technical illustrator.

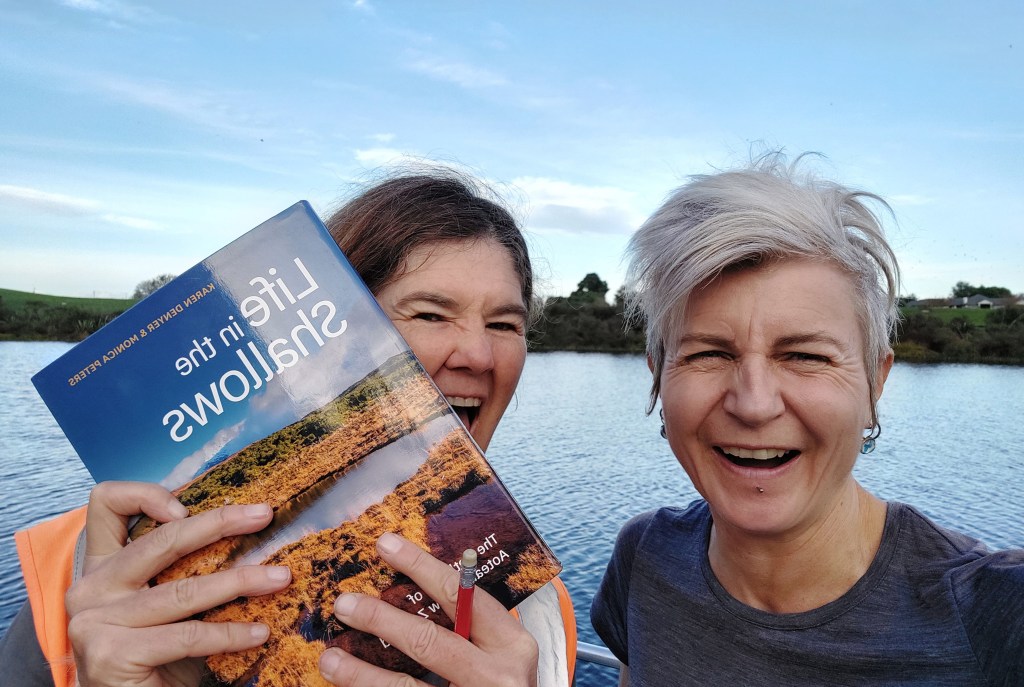

Then there’s writing about scientists. An opportunity that arose to co-author a book about the wetlands of Aotearoa: those sometimes salty, sometimes freshwater zones where land and water merge, unusual plants grow, and cryptic creatures lurk. I interviewed the 17 scientists profiled “Life in the Shallows” in to uncover what makes them tick as people along with their areas of wetland expertise. Some research microscopic processes while others work at the landscape scale, unpacking the past, measuring change and building future scenarios. The book is filled with rich conversations and insights charts a candid journey from the wetlands of the Far North right throughout Aotearoa to Antarctica.

What we can and cannot hear

By way of wrapping up my part of the event, I presented an image of a tūī. Instantly recognisable, almost everyone has heard its extraordinary vocabulary of chortles, clonks, whistles and clicks. But looking a tūī in full song, it’s clear that we can’t hear many of the sounds – they lie beyond the human register. It may seem odd during a concert to ask the audience to consider what we can’t hear. It seemed fitting to pause and reflect on sound, and the lack of it, because hidden among the layers of complexity, is a sonic richness we can only guess at.

Pingback: Flights of Fancy: birds, our taonga, through music, image and storytelling | monicalogues·